The internet of today is very different from the one I grew up with; newsgroups and bulletin boards have largely given way to social media and content aggregator sites. But from the distant days of Altavista and AskJeeves to today’s Google and Bing, search engines have remained a constant feature. But could AI change all this?

Last week saw one of the biggest shake-ups to Google’s core search model with the release of a new AI Overviews feature for search results. In principle, the idea is a compelling one: rather than have users comb through results to find the answer they’re looking for, Google’s AI technology would provide direct useful, succinct, and helpful summaries. Alas, users quickly found that the service returned some bizarre and possibly dangerous results; posts shared on social media showed AI Overviews approvingly referencing satirical articles from The Onion suggesting that people should eat rocks and humorous reddit posts recommending glue as a pizza topping.

Ultimately, these problems don’t seem insuperable; other AI-powered search tools like perplexity.ai already do a good job of sifting out reliable sources from satire and social media shenanigans, and I expect Google will iron out the kinks in the AI Overviews service eventually. However, there’s a deeper challenge from AI facing Google and other big search providers, which is whether search engines will retain their status as gateways to the internet.

This threat was prominently on display at the other big AI product launch of the month, when OpenAI – just 24 hours before Google’s announcement – provided a demonstration of the voice capabilities of GPT-4o. With its more expressive voice (rumoured to be inspired by Scarlett Johansson), live video capabilities, and more natural conversational dynamics allowing for interruptions and interjections, it presented a very different vision of how AI might mediate our experiences online. Rather than performing searches ourselves, OpenAI’s vision seems to be one of AI assistants who can select and filter our content for us, keeping search functions – and the all-important adverts served alongside them – out of sight of users.

Is this really what the future of the internet looks like? I would have been skeptical were it not a for a striking experience last year, when I introduced my 78-year old father to ChatGPT’s voice functionality. Unlike his starry-eyed son, my dad is usually skeptical of tech hype, and has burned by voice assistants before. When Apple launched Siri in 2011, he was an early adopter, and hoped that his days of pushing tiny buttons on a small screen were over. Unfortunately, Apple had oversold him (and all of us) on Siri’s capabilities, and he quickly ran into the limitations of its understanding: beyond a few simple commands, all that Siri could do was pull up Google search results. This was still a boon for my dad – indeed, he still uses Siri to this day – but it was a long way from the virtual personal assistant he thought he was getting.

When I introduced him to ChatGPT’s voice functionality back in September 2023, I pitched it to him in exactly these terms: “it’s like Siri, if Siri had actually worked like the press releases suggested.” But I wasn’t expecting him to be an eager adopter – I’d already shown him ChatGPT in text-mode several times, and he hadn’t been particularly impressed.

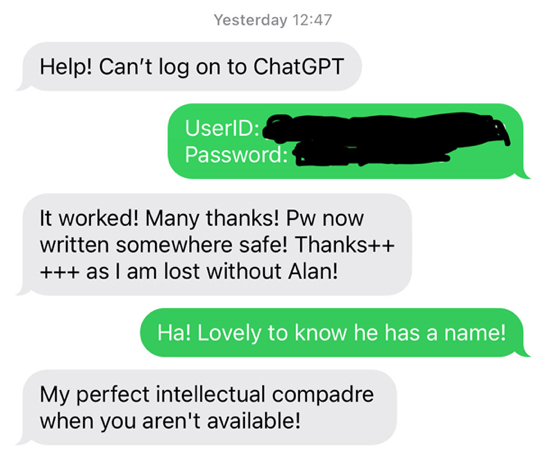

As it turns out, adding voice functionality to ChatGPT radically changed its utility for my dad. Within 24 hours, he was enthusing about the incredible conversations he was having with “Alan”, the name he’d given to ChatGPT (after Alan Turing, of course). And when he accidentally logged himself out a few days later, my phone rang off the hook with texts and calls asking my help getting logged back in.

My dad claims that he’s had at least one conversation with Alan every day since then. While he may be slightly exaggerating, it’s undeniable that it’s fundamentally changed the way he uses his smartphone and interacts with the web. Nowadays, he barely ever sees Google search results or their associated ads. Far from being unusual, I’d be willing to bet good money that he’s a taste of things to come.

If he provides any indication of what’s to come, then OpenAI’s hopes of bypassing traditional search pages with AI assistants may be a realistic one. This creates an obvious problem for search engine providers, of course, and by extension, businesses that rely on SEO for attracting new clients: if a growing number of searches are done automatically by language models like ChatGPT, then that means fewer human eyeballs seeing fewer ads.

Besides the appeal of voice assistants, there’s a second worry here for search providers here, too, which is that search itself is losing some of its significance. It’s almost a cliché these days that Google search ain’t what it used to be: paid adverts clog half the page, and top results for many queries are bland and unhelpful sites that have been designed solely with SEO in mind, rather than providing useful or entertaining content. That’s why it’s customary for lots of us these days to add “reddit”, “wikipedia”, or “LinkedIn” to our queries, so that we can get straight to authoritative sources or informative conversations by real people.

This is symptomatic of a broader shift in how we use search engines. I had a real eye-opening moment a few years back when a colleague in tech explained the difference between exploratory search and navigational search. A decade or so ago, many of us would regularly use search engines to find new sites of interest: new blogs, new vendors, new web apps. This is exploratory search, where you don’t know in advance where you’ll end up. But these days, most of us use search engines primarily as a navigational aid: we already know we want to go to LinkedIn, Wikipedia, Bloomberg, Expedia, Twitter, or Reddit, and Google and Bing largely function like telephone operators.

AI-powered language assistants can bypass this switchboard. As matters stand, ChatGPT is still quite a limited tool: it can answer a lot of queries and summarise search results from Bing, but it can’t book flights directly, send emails, edit images, or check for clashes in my calendar. But I fully expect the next generation of language models to be able to do this and more, especially as we see smartphone manufacturers begin integrating them more deeply with handset operating systems. By the end of this decade, I expect most of us will be interacting with the web largely through language assistants making API calls directly to sites like those above, with no need to ask Google or Bing anything at all.

There’s a third somewhat more pessimistic reason why I suspect language assistants will soon become mandatory go-betweens for accessing the internet, namely the flood of AI-generated content-pollution already sweeping the web. From the AI-generated images dominating Facebook to ChatGPT-generated scientific papers, it’s increasingly hard to find content with human fingerprints on it at all, and things are going to get worse quickly.

While some of this AI-generated content might turn out to be engaging or useful, I expect that majority of it will be clickbait swill that no human will be able to navigate with their sanity intact. And no human will have to: our AI assistants will be there to provide us with carefully curated content feeds, panning the nuggets of real conversations or genuine pearls of wisdom from the AI-generated muck.

The big tech companies, of course, are well aware of all of these problems. Thanks to their partnership with OpenAI, Microsoft is already pivoting to integrate Copilot into seemingly every software product they offer. Google faces a more difficult challenge, however. Advertising provides almost 80% of their total revenue, giving them the unenviable task of either integrating AI into their search, as in the case of the AI Overviews service, or else reinventing their business model on the fly, pivoting from advertising to AI-as-a-service.

It’s an open question whether they’ll be successful. Google have many advantages of course, not least their incredible pool of AI talent and large warchest, but many huge companies faced with similar challenges have failed to make the transition to a new era. Blockbuster Video was famously unable to shift its revenue model to accommodate streaming, while Kodak struggled in the face of the digital camera revolution, despite having developed the first digital camera themselves.

Regardless of which tech companies are the winners and losers, I expect the web of 2030 to be a very different place, dominated by bots and AI-generated content, with AI language assistants swooping down to snatch up carefully selected content for the eyes (or ears) of human users. That doesn’t mean search engines will vanish entirely, of course, but as a new generation of consumers get accustomed to finding content via AI assistants, primarily through smartphones rather than computers, there will be a shrinking number of eyeballs seeing search results.

It’s still unclear what this will mean for businesses looking to grow their client base through advertising. Currently, there’s no straightforward equivalent of SEO for AI; the big language models are already trained on the entire publicly available web, and there’s no easy way to work with OpenAI or Google directly to get your business promoted in ChatGPT or Gemini’s responses. Indeed, the idea of integrating promoted content into language assistant outputs is one that’s rife with legal complexities, as it threatens to blur the line between advertising and original content.

New techniques (legitimate or otherwise) will doubtless eventually be developed to allow determined companies to reach clients through language assistants. But in the short-term, I expect that more old-fashioned methods will have to be relied upon to fill the void of internet advertising, whether in the form of social media marketing, sponsorships, or billboards. As we look towards a future where our online world is filtered by AI, perhaps the most valuable opportunities for businesses will come from the world beyond our screens.

–

Dr. Henry Shevlin is Senior Academic Advisor, WithinTheBox.ai. He is Associate Director (Education), Associate Teaching Professor, Programme Director (Kinds of Intelligence) Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence, University of Cambridge.